Uncovering the True History of Thanksgiving

Much as I love Thanksgiving, I always experience a strong feeling of cognitive dissonance as I contemplate the huge gap between the spiritual message of gratitude for life's abundance and the cultural celebrations that overwhelm the spiritual component of the holiday with a completely different subtext.

According to the conventional story, strong, righteous English Puritans arrived at Plymouth Rock in 1620 in a ship called the Mayflower, arriving at a wilderness they called the New World. They brought what was considered to be a superior civilization and most important, their Christian values, to a thankless, scattered group of itinerant savages, and received turkeys, pumpkins, squash, corn and cranberry sauce in return.

Embarkation of the Pilgrims, Pilgrim Hall, Plymouth, Massacusetts, courtesy of New York Public Library

But that's just a pleasant myth that has become part of our consensus reality. The truth is quite a bit more complicated and bloody.

The original Thanksgiving, which occurred in 1621, is thought to be a celebration of the generosity of the Native American confederation of tribes known as the Wampanoag, some of whom spoke English, and introduced the clueless Puritans to corn and other New World crops the British had never seen before, crops that would save their New England colony from disaster.

In fact, white settlers in New England had attacked the Wampanoag tribes since 1524, taking slaves and capturing warriors and others to serve as interpreters and guides.

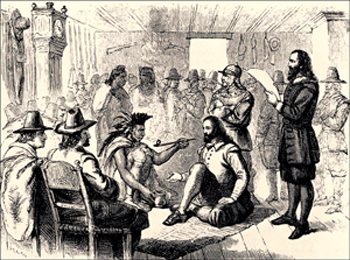

By 1616, European ships containing rats infected with European viruses had transmitted novel diseases to the Wampanoag, wiping out a large segment of their population. By 1619, other tribes began to raid the weakened Wampanoag, who sought out the Plymouth settlers in 1620 at Thanksgiving in hopes of enlisting the Puritans as allies in a widening inter-tribal war. The Wampanoag messenger named Squanto who negotiated with the settlers in their native tongue had spent years as a captive in Spain and England, and was well prepared for his role as mediator.

The Puritans were outnumbered by the Native Americans at the first Thanksgiving in 1621, and a treaty was signed, but the autumnal feast did not become a yearly festival. In fact relations between the white settlers and the Wampanoag tribes deteriorated. Fifteen years after the first Thanksgiving, English and Dutch fur traders seeking to control the region that produced their lucrative product triggered a war with numerous Native American tribes. By 1638, the white settlers had won the Pequot war. The majority of the allied Native American tribes had been either killed or taken and sold as slaves.

Charles Stanley Reinhart (1844–1896), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Following the 1637 massacre 500 Wampanoag men, women and children in a Native American village, William Bradford, the Governor of the Puritan colony of Plymouth wrote that for “the next 100 years, every Thanksgiving Day ordained by a Governor was in honor of the bloody victory, thanking God that the battle had been won.”

Somehow the 21st century version of Thanksgiving has deleted the massacre, the wars, and the genocide from our collective consciousness.

Modern Thanksgiving has become a celebration of conspicuous consumption, the beginning of a month-long orgy of Christmas shopping, and a spectacular collective celebration of the joys of corporate culture.

Each year on Thanksgiving, Jane and I join in a virtual commons of like-minded, passive viewers watching a media spectacle designed to forge emotional links between consumers and corporations sponsoring massive parades and a succession of football games shown on TV night and day all weekend long.

The towering air-filled balloons march through Midtown Manhattan, and file across the TV screen, filling my living room, as we munch on breakfast and sip on hot sugary caffeinated liquids. Prior to feasting and football, we participate in a nationwide homage to the omnipresence of the brand icons of trans-national corporations, an autumnal national celebration of consumer culture and of Madison Avenue's ability to mesmerize children, of all ages, with pastel kitsch cartoon characters emoting warm and fuzzy sentimentality that jerks the heartstrings while imprinting a series of corporate logos in the brains of viewers everywhere.

There is a subtext, and that is that the imagination will be subordinated to the advertising message, that on the Friday after Thanksgiving, the entire nation of 328,000,000 will awaken as one, with a druggy food hangover, climb in our SUVs and race to the shopping malls to begin a marathon orgy of compulsive spending and acquisition, which will climax on or about the festival commemorating the birthday of Jesus Christ.

Throughout this schizophrenic “holiday season”, our excessive spending and overconsumption of food, drink and electronic media are implied to be a gargantuan love offering to the Divine and, simultaneously, a concrete expression of the gratitude we all feel to our cultural forbears and an affirmation of the rampant materialism of our consumer culture.

In addition, it is through the holiday shopping rituals that we acquire the sacraments of conspicuous consumption, the newest electronic devices, fashions and other markers of material success -- the fetishes of our materialist culture.

We all know that the acquisition of the newest toys, trinkets, TVs and "smart" telephones is a vital activity for all Americans -- defining our status, our personality, our aesthetic sense, even constituting our deepest social identity.

Virtue is visible in America. In fact, virtue generates its own spectacle. We are what we buy! You can easily spot the winners in our culture by the logos on their clothes, their cars, their computers, phones and handbags. And the winners are considered to be not just smart or lucky, but virtuous. Yes, our culture teaches us that virtue is equivalent to wealth.

America’s current cultural mythology of social Darwinism and free market capitalism holds that competition among individuals to enrich themselves at the expense of others and the commons is the God-given right and the moral duty of all people, because in the Bible God made Adam and Eve stewards of the Earth, and all that lives upon it. A good steward must improve the property, so to speak. So individual profit seeking activities such as exploiting natural resources could even be considered a Biblical mandate.

This economic war of all against all will result in a Divinely ordered society, with the most deserving individuals conspicuous by virtue of their wealth and 10,000 square foot McMansions, and the least deserving individuals marked with the unmistakable stigmata of their moral failure, apparent to all in their lack of material possessions.

This is not originally an American narrative, rather its origins can be sought in the religious and political wars of 17th century England, where competing interpretations of Biblical narratives by Catholic and Protestant Christians triggered bloody wars across all of Europe and throughout the United Kingdom.

The Rise of Puritan England & the English Civil War

In the 1600s in England, a civil war was brewing between the traditional society and the adherents of a revolutionary, fundamentalist Protestant sect called the Puritans. At that time the Church of England was the official state-approved religion and Catholic priests and competing Protestant preachers had to operate as kind of spiritual undergound, subject to harassment of all kinds.

From 1625 to 1649 King Charles ruled supreme, and Parliament was an advisory body with few powers, called to meetings upon such occasions as the King determined appropriate. Charles I represented the Old Order of the Middle Ages. His crown had after all created the Church of England for personal convenience and as an instrument of State control.

The Puritans were Radicals. They believed that the individual had the right to read the Bible and interpret it for themselves. They also agreed with Calvin that the head of the Christian Church was neither the Pope of Rome nor the Arch-Bishop of Canterbury, but rather Jesus Christ. And Jesus lived in the Bible. So the interpretation of the Bible became the touchstone for all areas of life. The Congregationalists believed that the Divine Right of Kings was heresy, a belief that would come to bedevil Charles I during a decade of civil wars that would result in his downfall.

The Puritans believed they were the few righteous saints in a society of corrupt sinners, burdened excessively by the rapacious parasitism of King, nobility and court-approved clergy, and that only by forcing their own religious beliefs on their less spiritually evolved neighbors could the nation be saved. If that involved the liberal use of fire and sword and vast "collateral damage" to the general populace, then so be it. In fact, the Puritans expected war. Not just any war, but a big war, the war to end all wars.

Puritans expected Armageddon – the Apocalypse foretold in the more metaphorical chapters of the Bible –- to come -- momentarily, resulting in the destruction of all of Christendom, and hence of all civilization.

This Puritan vision of Armageddon involved, as Armageddon always has, the necessity for the faithful to wage a holy war against all unbelievers. This holy war would, first of all, overthrow the decadent elite that ran England, including parliament, King and priests, and second, impose a severe rule of autocratic but divinely guided cleric-warriors upon the sinful populace, driving Satan from their breasts through the use of panoptic espionage in every village and town, forced confession, and purgation through the salutary example of public torture and execution, as appropriate.

The Puritans believed that the "saints" who led this spiritual and very worldly revolution would be blessed by God with every social advantage, especially wealth, since Puritans were industrious believers in the blessings of free markets as well as being devout Christians. They further believed that individuals who failed to create sufficient wealth to feed their families and themselves through competitive enterprise were inherently sinful, self-evidently guilty of moral failure, and should be punished by confinement to debtor prisons and other “tough love” institutions where reprogramming of their defective nervous systems could proceed unhindered by false notions of “charity”, “compassion”, “noblesse oblige” and “social welfare”.

They were armed with an Apocalyptic, dualistic, militarized religion that glorified profit-taking and called it "enlightened self-interest". One might call this an early form of Utopian capitalism before capitalism was even well-defined. Over the next hundred years, this Puritan philosophy of business minded zeaots would produce the basic tenets of free market capitalism as we know it today. Theorists of the new mercantile order that supplanted the old medieval order assumed that the sum total of all self-interested individual economic transactions, conducted without regard for their effects on the broader society or the environment, would result in the best of all possible worlds, a world guided by the "invisible hand" of the marketplace rather than by moral codes or spiritual principles.

This was in a way considered to be "enlightened" thinking at that time, as Christendom slowly tried to ascend out of the Dark Ages, because it was assumed that all actors in the free market were rational and logical in calculating and in transacting their business.

Thus, the free market embodied the collective logical and rational calculations of the best minds in the marketplace. Naturally such a collective consciousness could be assumed to be ultimately infallible in its wisdom, and thus the individuals who profited the most from the resulting economic system would by definition be the most worthy individuals, the most virtuous, the smartest, the best fitted for survival, etc. etc. etc.

So it was a radical departure to assume that the collective consciousness of the business community could substitute its wisdom for the rules and regulations governing markets and business practices that had been traditionally imposed upon princes, merchants, farmers and craftsmen by the dominant Christian churches, Catholic and Church of England alike, since the Middle Ages. The new doctrines of the Puritans coud not be reconciled with the Divine Right of Kings, the primacy of the Church of England and the old order generally.

After a series of Civil Wars, starting in 1639, the Puritans did overthrow the King of England in 1649, in a bloody revolution led by the Puritan leader Oliver Cromwell. Around ten percent of the total population of England, Ireland and Scotland died during these apocalyptic battles.

After a series of Civil Wars, starting in 1639, the Puritans did overthrow the King of England in 1649, in a bloody revolution led by the Puritan leader Oliver Cromwell. Around ten percent of the total population of England, Ireland and Scotland died during these apocalyptic battles.

The reformist political projects of the Puritan victors were set aside in the aftermath of these civil wars, and Cromwell ruled as a military dictator until his death.

The intolerance, arrogance and aggressive individualistic egotism of the Puritans led them from an initial enlightened attitude toward the right of the individual to have a personal relationship with the Divine, and a healthy respect for the powers of the emerging rational intellect and scientific method, to a social structure which later ceded dictatorial powers to individuals who represented both civil and religious authority simultaneously.

Today, a similar flavor of militaristic religious zeal grips the more right-wing political parties in America, Europe, Iran, Pakistan, Israel, and India. Large groups in all these countries exhibit highly intolerant fundamentalist religious beliefs and have strong ties to Godzilla-sized aggressive national military bureaucracies with long histories of military adventurism. The political and economic elites in all these countries have total faith in today's neo-liberal version of Utopian capitalism, known as globalization, despite the 2008 Global Financial Meltdown and the ensuing 21st Century Depression we are now enduring.

Cromwell's son was considered unfit by the Army, which constituted the true ruling class of England at that point, and chaos threatened until 1661, when Charles’ son, Charles II, was restored to the throne, with the consent of Parliament.

No longer able to rule as a Sovereign without peers, Charles II found the country set on a course to become a parliamentary democracy that practiced a determined form of religious tolerance.

Meanwhile, in the New World, the Puritans were also involved in another flavor of Armageddon. Some of those "enlightened" Pilgrims who migrated to America lacked the surety of faith that would have enabled them to believe in the historical inevitability of the English Puritan Revolution, and some of them doubtless saw themselves as God’s Crusaders, spreading the Word of God and a New Social Order to a New, Godless and heathen world, which must be conquered for the greater glory of God, as part of the Apocalyptic War between Good and Evil.

In America, in states where they gained power, Puritans made sure there were no illusions of religious freedom. The just rule of iron and fire was thought to guarantee a salutary social uniformity that would be pleasing to the stern and vengeful patriarch in heaven.

When the Pilgrim colonists arrived in New England, landing at Plymouth Rock in 1620, the area was the home of the Wampanoag Indians, members of a widespread Confederacy of Algonkian speaking peoples known as the League of the Delaware. For over one hundred years, the Wampanoag had defended themselves against sporadic incursions by European slave traders, trappers and soldiers, so they were familiar with the predatory nature of the white colonizers.

In Massachusetts, in 1620, Puritan colonists signed the Mayflower Compact, which bound all signatories to the letter and the law of early Christian practice, Puritan practice, and banished Catholic and Episcopalian ritual and observances. All males who wished to live in the colony had to sign the Compact.

Later Puritan dissenters, including Roger Williams, who founded the Baptist Church, and Anne Hutchinson, a prominent Puritan gentlewoman who held that matters of faith were private affairs between each individual and God, were banished from the colony.

In 1636 Roger Williams, the founder established a new colony in Rhode Island, where all true believing Protestants could participate in civil government, though not, of course, the Godless Catholic idolators.

It was the Catholics, who had brought the world the original practice of enlightenment through torture exemplified in the Inquisition, who introduced the American Colonies to the principle of religious tolerance, which was a matter of law in the Catholic colony of Maryland.

The Wampanoag continued their traditional way of life during this period, migrating from place to place as the seasons unfolded. In the spring, the Indians would pitch their wigwams near rivers, fishing for herring and salmon. In planting season they moved to the forest, where they could hunt deer. In winter they moved inland for protection from the inclement weather, and lived on stores of food gathered earlier in the year.

Wisdom Ways of the Wampanoag People

Gratitude was an integral part of everyday life for the Wampanoag Indians, not something to be ritually celebrated once a year.

As historian and public school teacher Chuck Larsen, who has Quebeque French, Metis, Ojibwa, and Iroquois ancestors puts it in his article on Thanksgiving, “These Indians of the Eastern Woodlands called the turtle, the deer and the fish their brothers. They respected the forest and everything in it as equals. Whenever a hunter made a kill, he was careful to leave behind some bones or meat as a spiritual offering, to help other animals survive. Not to do so would be considered greedy. The Wampanoags also treated each other with respect. Any visitor to a Wampanoag home was provided with a share of whatever food the family had, even if the supply was low. This same courtesy was extended to the Pilgrims when they met.”

Larsen continues:

“We can only guess what the Wampanoags must have thought when they first saw the strange ships of the Pilgrims arriving on their shores. But their custom was to help visitors, and they treated the newcomers with courtesy. It was mainly because of their kindness that the Pilgrims survived at all. The wheat the Pilgrims had brought with them to plant would not grow in the rocky soil. They needed to learn new ways for a new world, and the man who came to help them was called ‘Tisquantum’ (Tis SKWAN tum) or ‘Squanto (SKWAN toe).

“Squanto was originally from the village of Patuxet (Pa TUK et) and a member of the Pokanokit Wampanoag nation. Patuxet once stood on the exact site where the Pilgrims built Plymouth . In 1605, fifteen years before the Pilgrims came, Squanto went to England with a friendly English explorer named John Weymouth. He had many adventures and learned to speak English. Squanto came back to New England with Captain Weymouth. Later Squanto was captured by a British slaver who raided the village and sold Squanto to the Spanish in the Caribbean Islands . A Spanish Franciscan priest befriended Squanto and helped him to get to Spain and later on a ship to England. Squanto then found Captain Weymouth , who paid his way back to his homeland. In England Squanto met Samoset of the Wabanake (Wab NAH key) Tribe, who had also left his native home with an English explorer. They both returned together to Patuxet in 1620. When they arrived, the village was deserted and there were skeletons everywhere. Everyone in the village had died from an illness the English slavers had left behind. Squanto and Samoset went to stay with a neighboring village of Wampanoags.

“One year later, in the spring, Squanto and Samoset were hunting along the beach near Patuxet. They were startled to see people from England in their deserted village. For several days, they stayed nearby observing the newcomers. Finally they decided to approach them. Samoset walked into the village and said ‘welcome,’ Squanto soon joined him. The Pilgrims were very surprised to meet two Indians who spoke English.

“The Pilgrims were not in good condition. They were living in dirt-covered shelters, there was a shortage of food, and nearly half of them had died during the winter. They obviously needed help and the two men were a welcome sight.

"Squanto, who probably knew more English than any other Indian in North America at that time, decided to stay with the Pilgrims for the next few months and teach them how to survive in this new place. He brought them deer meat and beaver skins. He taught them how to cultivate corn and other new vegetables and how to build Indian-style houses. He pointed out poisonous plants and showed how other plants could be used as medicine. He explained how to dig and cook clams, how to get sap from the maple trees, use fish for fertilizer, and dozens of other skills needed for their survival.

“By the time fall arrived things were going much better for the Pilgrims, thanks to the help they had received.

"The corn they planted had grown well. There was enough food to last the winter. They were living comfortably in their Indian-style wigwams and had also managed to build one European-style building out of squared logs. This was their church. They were now in better health, and they knew more about surviving in this new land. The Pilgrims decided to have a thanksgiving feast to celebrate their good fortune. They had observed thanksgiving feasts in November as religious obligations in England for many years before coming to the New World .

“The Algonkian tribes held six thanksgiving festivals during the year. The beginning of the Algonkian year was marked by the Maple Dance which gave thanks to the Creator for the maple tree and its syrup. This ceremony occurred when the weather was warm enough for the sap to run in the maple trees, sometimes as early as February. Second was the planting feast, where the seeds were blessed. The strawberry festival was next, celebrating the first fruits of the season. Summer brought the green corn festival to give thanks for the ripening corn. In late fall, the harvest festival gave thanks for the food they had grown. Mid-winter was the last ceremony of the old year. When the Indians sat down to the ‘first Thanksgiving’ with the Pilgrims, it was really the fifth thanksgiving of the year for them!

“Captain Miles Standish, the leader of the Pilgrims, invited Squanto, Samoset, Massasoit (the leader of the Wampanoags), and their immediate families to join them for a celebration, but they had no idea how big Indian families could be. As the Thanksgiving feast began, the Pilgrims were overwhelmed at the large turnout of ninety relatives that Squanto and Samoset brought with them. The Pilgrims were not prepared to feed a gathering of people that large for three days. Seeing this, Massasoit gave orders to his men within the first hour of his arrival to go home and get more food. Thus it happened that the Indians supplied the majority of the food: Five deer, many wild turkeys, fish, beans, squash, corn soup, corn bread, and berries. Captain Standish sat at one end of a long table and the Clan Chief Massasoit sat at the other end. For the first time the Wampanoag people were sitting at a table to eat instead of on mats or furs spread on the ground. The Indian women sat together with the Indian men to eat. The Pilgrim women, however, stood quietly behind the table and waited until after their men had eaten, since that was their custom.

“Captain Miles Standish, the leader of the Pilgrims, invited Squanto, Samoset, Massasoit (the leader of the Wampanoags), and their immediate families to join them for a celebration, but they had no idea how big Indian families could be. As the Thanksgiving feast began, the Pilgrims were overwhelmed at the large turnout of ninety relatives that Squanto and Samoset brought with them. The Pilgrims were not prepared to feed a gathering of people that large for three days. Seeing this, Massasoit gave orders to his men within the first hour of his arrival to go home and get more food. Thus it happened that the Indians supplied the majority of the food: Five deer, many wild turkeys, fish, beans, squash, corn soup, corn bread, and berries. Captain Standish sat at one end of a long table and the Clan Chief Massasoit sat at the other end. For the first time the Wampanoag people were sitting at a table to eat instead of on mats or furs spread on the ground. The Indian women sat together with the Indian men to eat. The Pilgrim women, however, stood quietly behind the table and waited until after their men had eaten, since that was their custom.

“For three days the Wampanoags feasted with the Pilgrims. It was a special time of friendship between two very different groups of people. A peace and friendship agreement was made between Massasoit and Miles Standish giving the Pilgrims the clearing in the forest where the old Patuxet village once stood to build their new town of Plymouth.

“For three days the Wampanoags feasted with the Pilgrims. It was a special time of friendship between two very different groups of people. A peace and friendship agreement was made between Massasoit and Miles Standish giving the Pilgrims the clearing in the forest where the old Patuxet village once stood to build their new town of Plymouth.

[The 1621 feast the Wampanoag gave the Pilgrims Indians was not the official first Thanksgiving. That title goes to a 1637 celebration, proclaimed “Thanksgiving” by Governor Winthrop, an event honoringthose who participated in the massacre of the 700-800 Pequot Indians in Connecticut .]

Larsen continues, “It would be very good to say that this friendship lasted a long time; but, unfortunately, that was not to be. More English people came to America, and they were not in need of help from the Indians as were the original Pilgrims. Many of the newcomers forgot the help the Indians had given them. Mistrust started to grow and the friendship weakened. The Pilgrims started telling their Indian neighbors that their Indian religion and Indian customs were wrong. The Pilgrims displayed an intolerance toward the Indian religion similar to the intolerance displayed toward the less popular religions in Europe . The relationship deteriorated and within a few years the children of the people who ate together at the first Thanksgiving were killing one another in what came to be called King Phillip's War.

“At the end of that conflict most of the New England Indians were either exterminated or refugees among the French in Canada, or they were sold into slavery in the Carolinas by the Puritans. So successful was this early trade in Indian slaves that several Puritan ship owners in Boston began the practice of raiding the Ivory Coast of Africa for black slaves to sell to the proprietary colonies of the South, thus founding the American-based slave trade.

On June 20, 1676 - following the victory over King Philip and his people - the council of Charlestown , Massachusetts unanimously voted to proclaim June 29 as a day of celebration and Thanksgiving. The following statement was read:

"The Holy God having by a long and Continual Series of his Afflictive dispensations in and by the present Warr with the Heathen Natives of this land, written and brought to pass bitter things against his own Covenant people in this wilderness, yet so that we evidently discern that in the midst of his judgments he hath remembered mercy, having remembered his Footstool in the day of his sore displeasure against us for our sins, with many singular Intimations of his Fatherly Compassion, and regard; reserving many of our Towns from Desolation Threatened, and attempted by the Enemy, and giving us especially of late with many of our Confederates many signal Advantages against them, without such Disadvantage to ourselves as formerly we have been sensible of, if it be the Lord's mercy that we are not consumed, It certainly bespeaks our positive Thankfulness, when our Enemies are in any measure disappointed or destroyed; and fearing the Lord should take notice under so many Intimations of his returning mercy, we should be found an Insensible people, as not standing before Him with Thanksgiving, as well as lading him with our Complaints in the time of pressing Afflictions.”

Larsen continues, “It is sad to think that this happened, but it is important to understand all of the story and not just the happy part. Today the town of Plymouth Rock has a Thanksgiving ceremony each year in remembrance of the first Thanksgiving. There are still Wampanoag people living in Massachusetts. In 1970, they asked one of them to speak at the ceremony to mark the 350th anniversary of the Pilgrim's arrival. Here is part of what was said:

"Today is a time of celebrating for you -- a time of looking back to the first days of white people in America . But it is not a time of celebrating for me. It is with a heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my People. When the Pilgrims arrived, we, the Wampanoags, welcomed them with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end. That before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a tribe. That we and other Indians living near the settlers would be killed by their guns or dead from diseases that we caught from them. Let us always remember, the Indian is and was just as human as the white people.

"Today is a time of celebrating for you -- a time of looking back to the first days of white people in America . But it is not a time of celebrating for me. It is with a heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my People. When the Pilgrims arrived, we, the Wampanoags, welcomed them with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end. That before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a tribe. That we and other Indians living near the settlers would be killed by their guns or dead from diseases that we caught from them. Let us always remember, the Indian is and was just as human as the white people.

“Although our way of life is almost gone, we, the Wampanoags, still walk the lands of Massachusetts. What has happened cannot be changed. But today we work toward a better America, a more Indian America where people and nature once again are important."

“Our contemporary mix of myth and history about the ‘First’ Thanksgiving at Plymouth developed in the 1890s and early 1900s. Our country was desperately trying to pull together its many diverse peoples into a common national identity. To many writers and educators at the end of the last century and the beginning of this one, this also meant having a common national history. This was the era of the ‘melting pot’ theory of social progress, and public education was a major tool for social unity. It was with this in mind that the federal government declared the last Thursday in November as the legal holiday of Thanksgiving in 1898.

“In consequence, what started as an inspirational bit of New England folklore, soon grew into the full-fledged American Thanksgiving we now know. It emerged complete with stereotyped Indians and stereotyped Whites, incomplete history, and a mythical significance as our ‘First Thanksgiving’,” Larsen concludes.

We're All Puritans Now

Today, in the 2020s,, the American Empire is hitting a rough patch, just as the British Monarchy did in the 1600s, a time when King Charles I had to deal with both internal conflict and foreign wars simultaneously with ongoing financial crises brought about by overspending.

America's Wall Street brain trust blew up the global financial system in 2008, and then blackmailed President Obama into a $10+ trillion bailout of America's biggest Wall Street institutions and banks and our country's wealthiest investors. A decade later, during the 2020 Covid crisis, the financial fallout from economic lockdowns triggered another $4 trillion in bailouts of large corporations and banks.

Charles I of England, Oil Portrait by Follower of Anthony van Dyck , Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Like Charles I, America is at risk of losing its crown. America and her allies are in financial trouble and America is engaged in multiple wars around the world during the most drastic man-made global environmental crisis ever to confront our species.

And as in the time of Charles I, the aristocracy that rules our American Empire has kleptomaniac, megalomaniac, and Imperial tendencies.

American Presidents in the 21st century have begun to emulate Charles I, who raised money for wars through what were called ""forced loans"", taxes to be levied without Parliamentary consent, imposed martial law on civilians, imprisoned them without due process, and quartered troops in civilian homes.

Charles I eventually was forced by Parliament to relinquish these broad, dictatorial powers, but there is no indication that today's American Congress would challenge the President's perogatives -- to assassinate American citizens and individuals of all other nationalities at will, to impose military tribunals at will upon anyone anywhere in the world, and to engage in un-Constitutional surveillance, searches and seizures of American citizens in their homes, workplaces and in public spacs as well.

The modern day ancestors of Charles I and of the Puritan inquisitors who opposed the King have united in a 21st century attempt to create a total surveillance society, a high-tech version of the Panopticon, a prison building designed by British philosopher Jeremy Bentham to facilitate surveillance.

The original design of the Panopticon features a circular structure with a central surveillance tower, which allows staff to watch the inmates housed around the perimeter of the building, without the inmates being aware of the surveillance.

![]()

Plan of Jeremy Bentham's Panopticon Prison, Blue Ākāśha, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Many modern prisons resurrect and refine the Panopticon design, with pods or modules housing prisoners laid out in tiers around a central ""control station"" which affords a single corrections officer with a full view of the cells nearby, augmented by CCTV cameras and electronic cell door controls.

And prisons are only a model for an extreme example of the modern surveillance society. The Puritans valued surveillance of their citizens and established elaborate systems of control featuring torture and banishment and worse, but neither Charles I nor his most inquisitorial Puritan enemies would believe what we have achieved with 21st century surveillance technologies. Nothing in their wildest dreams could have prepared them for the degree of remote control today's corporations and governments can exert on the general public.

The impulse toward total surveillance and control has been extended from prisons to airports, central business districts of large cities, and now the entire global Internet. Modern day Americans have become used to the idea that their phones, email, and text messages can and will be monitored by both corporate marketing wizards and governmental agents. We don't mind taking off shoes and belts at airports or being X-Rayed before we board an airplane. We expect video surveillance cameras to follow our movements in downtowns, shopping malls, parking lots, offices, schools, and even in our own homes, if we are affluent enough to afford our own personal home surveillance and CCTV systems.

A monitor wall with fifteen 42-inch monitors for 176 on-street cameras in a public space CCTV control room

Mark Yeomans, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Who will wield the power of the post-modern Apocalyptic Panopticon of the near future? Will it be a neo-Puritan fundamentalist Christian militarized American Global Panopticon?

Will it be a corporate fascist neo-liberal economic Panopticon centered upon your smartphone, which tracks every dime you get and spend, where you were when you got and spent it, and probably who you were with, what you emailed, texted and who you called. Plus other stuff too numerous to mention?

Will it be a well-intentioned liberal Nanny state Panopticon where high-IQ technocrats impose their vision of a low-budget self-help social welfare state to fund Imperial wars around the world?

Or will we create a different future, free of the dead hand of mythologies of mass destruction, greed masquerading as ""enlightenment"", and, most important of all, free from that peculiar failure of the heart that always sees more bloodshed as the solution to all social problems.

Perhaps this Thanksgiving we could all set aside a few minutes to ponder the story of the first Thanksgiving more deeply.

Let us free ourselves from our normal cultural triumphalism, and acknowledge that the Wampanoag showed the Puritans the true meaning of Christian charity at the first Thanksgiving. The Wampanoag were repaid with genocide.

Let us all meditate upon that sequence of events and find within our hearts the humility and gratitude that embody the true meaning of Thanksgiving.

Why did the Puritans behave so badly? The Puritan blend of militaristic religious zeal and free-market mercantile Messianism created a feeling of arrogant exceptionalism among the British in America that first Thanksgiving. Although their colony was failing, the Puritans knew that they were the chosen people, and that their duty was to spread their religion and their political and economic system throughout the world, using fire and sword as needs be.

They failed to appreciate, understand, or honor the gifts, the wisdom, and the culture of the Native Americans.

Today all the peoples of the world who participate in our global economy stand in the shoes of the Puritans, at least to some extent. For those of us living in advanced economies and countries have forgotten the message of the Wampanoag. We have dishonored Mother Earth and we have removed her stewards from positions of power and authority within our culture.

We in the most advanced countries on Earth have created aggressively militarized societies featuring large cohorts of religious fundamentalists who promote aggressive policies toward their perceived enemies, and economic systems that reward individual profit-taking above all, without regard for the social or environmental consequences.

We are much more like the Puritans than the Wampanoag. All high-tech globalized members of Earth's consumer culture in every country in the world, no matter what their religion, political affiliations, or racial background, have more in common with the Puritans than the Wampanoag.

This Thanksgiving let us all pray that the Wisdom of the Wampanoag will spread throughout the world, and that the more ""advanced"" civilizations of the world will begin to understand that no culture can survive and thrive except through honoring Mother Earth, the cycles of life, the Family of Humanity, and the Beings who live in mineral, plant and animal bodies everywhere under the Sun.

Meditation Moment: Giving Thanks to the Wampanoag

Let us give thanks to the Wampanoag Indian tribe for their charity to the English Puritans over 300 years ago. Let us try to learn from their values.

Let us meditate upon the need for a return to the values of the Wampanoag. Let us consider how the values of the Wampanoag are in many ways, similar to the values of the Buddha.

Compassion for all sentient beings. Respect for the land.

The Dharmachakra contains Buddha's Teachings, courtesy Wikimedia![]()

Constant ritual connection to the Wheel of Life, the seasons of the year, the needs of the community.

Generosity as a marker of wealth, not conspicuous consumption.

An ability to see beneath the surface to the living heart of people, and to truly know the difference between appearance and reality.

Let us ask that humanity's heart and mind be opened to the ancient Wisdom Teachings, ask that we learn to Love and Honor our Mother Earth and one another. This Thanksgiving we pray for an end to genocide, and end to racial and religious intolerance. This Thanksgiving we give thanks that there is still time for humanity to learn to live in peace with one another and on our blue green planet.

This Thanksgiving we pray that we all remember--we are the caretakers!! We are the stewards, we are one community, one neighborhood, one world.

Let us all pray for discernment this Thanksgiving, for in times like these, discernment is perhaps the most important mental virtue.

Much love to you all from Curtis and Jane!