CIA, Big Oil, Heroin and Al Qaeda

[Satya Center is proud to present this excerpt from a book written by world-renowned investigative author Peter Dale Scott entitled "The Road to 9/11".

Dr. Scott's previous books include "Drugs Oil and War", "Cocaine Politics: Drugs, Armies, and the CIA in Central America", "The Iran-Contra Connection: Secret Teams and Covert Operations in the Reagan Era, Deep Politics II": "Oswald, Mexico and Cuba", "The Assassinations: Dallas and Beyond -- A Guide to Cover-Ups and Investigations", and "Deep Politics and the Death of JFK".]

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Road to 9/11: Chapter 8

Al Qaeda and the U.S. Establishment

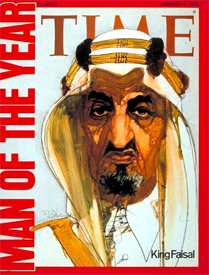

The then leader of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, Sayed Kuttub, a man Faisal sponsored to undermine Nasser, openly admitted that during this period [the 1960s] “America made Islam.” [1]

The then leader of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, Sayed Kuttub, a man Faisal sponsored to undermine Nasser, openly admitted that during this period [the 1960s] “America made Islam.” [1]

What is slowly emerging from Al Qaeda activities in Central Asia in the 1990s is the extent to which they involved both American oil companies and the U.S. government.[2] By now we know that the U.S. protected movements of al Qaeda terrorists into regions like Afghanistan, Azerbaijan and Kosovo have served the interests of U.S. oil companies. In many cases they have also provided pretexts or opportunities for a U.S. military commitment and even troops to follow.

This has been most obvious in the years since the Afghan War with the Soviet Union ended in 1989. Deprived of Soviet troops to support it, the Soviet-backed Najibullah regime in Kabul finally fell in April 1992. What should have been a glorious victory for the mujahedin proved instead to be a time of troubles for them, as Tajiks behind Massoud and Pashtuns behind Hekmatyar began instead to fight each other.

The situation was particularly difficult for the Arab Afghans, who now found themselves no longer welcome. Under pressure from America, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia, the new interim president of Afghanistan, Mojaddedi, announced that the Arab Afghans should leave. In January 1993 Pakistan followed suit, closed the offices of all mujahedin in its country, and ordered the deportation of all Arab Afghans.[3] Shortly afterwards Pakistan extradited a number of Egyptian jihadis to Egypt, some of whom had already been tried and convicted in absentia.[4] Other radical Islamists went to Afghanistan, but without the foreign support they had enjoyed before.

Fleeing the hostilities in Afghanistan, some Uzbek and Tajik mujahedin and refugees started fleeing or returning north across the Amu Darya.[5] In this confusion, with or without continued U.S. backing, cross-border raids, of the kind originally encouraged by CIA Director Casey back in the mid-1980s, continued.[6] Both Hekmatyar and Massoud actively supported the Tajik rebels, including in the years up to 1992 when both continued to receive aid and assistance from the United States.[7] The Pakistani observer Ahmed Rashid documents further support for the Tajik rebels from both Saudi Arabia and the Pakistani intelligence directorate ISI.[8]

These raids into Tajikistan and later Uzbekistan contributed materially to the destabilization of the MuslimRepublics in the Soviet Union (and after 1992 of its successor, the Conference of Independent States). This destabilization was an explicit goal of U.S. policy in the Reagan era, and did not change with the end of the Afghan War.  On the contrary, the United States was concerned to hasten the break-up of the Soviet Union, and increasingly to gain access to the petroleum reserves of the CaspianBasin, which at that time were still estimated to be “the largest known reserves of unexploited fuel in the planet.”[9]

On the contrary, the United States was concerned to hasten the break-up of the Soviet Union, and increasingly to gain access to the petroleum reserves of the CaspianBasin, which at that time were still estimated to be “the largest known reserves of unexploited fuel in the planet.”[9]

Eventually the threat presented by Islamist rebels persuaded the governments of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan to allow U.S. as well as Russian bases on their soil. The result is to preserve artificially a situation throughout the region where small elites grow increasingly wealthy and corrupt, while most citizens suffer from a sharp drop in living standards.[12]

The gap between the Bush Administration’s professed ideals and its real objectives is well illustrated by its position towards the regime of Karimov in Uzbekistan. America quickly sent Donald Rumsfeld to deal with the new regime in Kyrgyzstan installed in March 2005 after the popular “Tulip Revolution” and overthrow there of Askar Akayev.[13] But Islam Karimov’s violent repression of a similar uprising in Uzbekistan saw no wavering of U.S. support for a dictator who has allowed U.S. troops to be based in his oil- and gas-rich country.[14]

U.S. Operatives, Oil Companies and Al Qaeda in Azerbaijan

In one former Soviet Republic, Azerbaijan, Arab Afghan jihadis clearly assisted this effort of U.S. oil companies to penetrate the region. In 1991, Richard Secord, Heinie Aderholt, and Ed Dearborn, three veterans of U.S. operations in Laos, and later of Oliver North’s operations with the Contras, turned up in Baku under the cover of an oil company, MEGA Oil.[15] This was at a time when the first Bush administration had expressed its support for an oil pipeline stretching from Azerbaijan across the Caucasus to Turkey.[16] MEGA never did find oil, but did contribute materially to the removal of Azerbaijan from the sphere of post-Soviet Russian influence.

Secord, Aderholt, and Dearborn were all career U.S. Air Force officers, not CIA. However Secord explains in his memoir how Aderholt and himself were occasionally seconded to the CIA as CIA detailees. Secord describes his own service as a CIA detailee with Air America in first Vietnam and then Laos, in cooperation with the CIA Station Chief Theodore Shackley.[17] Secord later worked with Oliver North to supply arms and materiel to the Contras in Honduras, and also developed a small air force for them, using many former Air America pilots.18] Because of this experience in air operations, CIA Director Casey and Oliver North had selected Secord to trouble-shoot the deliveries of weapons to Iran in the Iran-Contra operation.[19] (Aderholt and Dearborn also served in the Laotian CIA operation, and later in supporting the Contras.)

Secord, Aderholt, and Dearborn were all career U.S. Air Force officers, not CIA. However Secord explains in his memoir how Aderholt and himself were occasionally seconded to the CIA as CIA detailees. Secord describes his own service as a CIA detailee with Air America in first Vietnam and then Laos, in cooperation with the CIA Station Chief Theodore Shackley.[17] Secord later worked with Oliver North to supply arms and materiel to the Contras in Honduras, and also developed a small air force for them, using many former Air America pilots.18] Because of this experience in air operations, CIA Director Casey and Oliver North had selected Secord to trouble-shoot the deliveries of weapons to Iran in the Iran-Contra operation.[19] (Aderholt and Dearborn also served in the Laotian CIA operation, and later in supporting the Contras.)

As MEGA operatives in Azerbaijan, Secord, Aderholt, Dearborn, and their men engaged in military training, passed “brown bags filled with cash” to members of the government, and above all set up an airline on the model of Air America which soon was picking up hundreds of mujahedin mercenaries in Afghanistan.[20] (Secord and Aderholt claim to have left Azerbaijan before the mujahedin arrived.) Meanwhile, Hekmatyar, who at the time was still allied with bin Laden, was “observed recruiting Afghan mercenaries [i.e. Arab Afghans] to fight in Azerbaijan against Armenia and its Russian allies.”[21] At this time, heroin flooded from Afghanistan through Baku into Chechnya, Russia, and even North America.[22] It is difficult to believe that MEGA’s airline (so much like Air America) did not become involved.[23]

The operation was not a small one.

Over the course of the next two years, [MEGA Oil] procured thousands of dollars worth of weapons and recruited at least two thousand Afghan mercenaries for Azerbaijan - the first mujahedin to fight on the territory of the former Communist Bloc.”[24]

In 1993 the mujahedin also contributed to the ouster of Azerbaijan’s elected president, Abulfaz Elchibey, and his replacement by an ex-Communist Brezhnev-era leader, Heidar Aliyev.

At stake was an $8 billion oil contract with a consortium of western oil companies headed by BP. Part of the contract would be a pipeline which would, for the first time, not pass through Russian-controlled territory when exporting oil from the Caspian basin to Turkey. Thus the contract was bitterly opposed by Russia, and required an Azeri leader willing to stand up to the former Soviet Union.

The Arab Afghans helped supply that muscle. Their own eyes were set on fighting Russia in the disputed Armenian-Azeri region of Nagorno-Karabakh, and in liberating neighboring Muslim areas of Russia: Chechnya and Dagestan.[25]  To this end, as the 9/11 Report notes (58), the bin Laden organization established an NGO in Baku, which became a base for terrorism elsewhere.[26] It also became a transshipment point for Afghan heroin to the Chechen mafia, whose branches “extended not only to the London arms market, but also throughout continental Europe and North America.”[27]

To this end, as the 9/11 Report notes (58), the bin Laden organization established an NGO in Baku, which became a base for terrorism elsewhere.[26] It also became a transshipment point for Afghan heroin to the Chechen mafia, whose branches “extended not only to the London arms market, but also throughout continental Europe and North America.”[27]

The Arab Afghans’Azeri operations were financed in part with Afghan heroin.

According to police sources in the Russian capital, 184 heroin processing labs were discovered in Moscow alone last year. ''Every one of them was run by Azeris, who use the proceeds to buy arms for Azerbaijan's war against Armenia in Nagorno- Karabakh,'' [Russian economist Alexandre] Datskevitch said.[28]

This foreign Islamist presence in Baku was also supported by bin Laden’s financial network.[29] With bin Laden’s guidance and Saudi support, Baku soon became a base for jihadi operations against Dagestan and Chechnya in Russia.[30]And an informed article argued in 1999 that Pakistan’s ISI, facing its own disposal problem with the militant Arab-Afghan veterans, trained and armed them in Afghanistan to fight in Chechnya. ISI also encouraged the flow of Afghan drugs westward to support the Chechen militants, thus diminishing the flow into Pakistan itself.[31]

[1]Saïd K. Aburish, The Rise, Corruption and Coming Fall of the House of Saud (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995), 130-31.

[2]Western governments and media apply the term “al Qaeda” to the whole “network of co-opted groups” who have at some point accepted leadership, training and financing from bin Laden (Jason Burke, Al-Qaeda: The True Story of Radical Islam [London: I.B. Tauris, 2004], 7-8). From a Muslim perceptive, the term “Al Qaeda” is clumsy, and has led to the targeting of a number of Islamist groups opposed to bin Laden’s tactics. See Montasser al-Zayyat, The Road to Al-Qaeda: The Story of Bin Lāden’s Right-Hand Man [London: Pluto Press, 2004], 100, etc.). I am reminded of certain right-wing hypostatizations of the Vietnam anti-war “Movement” in which I took part, and which saw foreign-funded conspiracy where I could only see chaos. For this reason I will where possible try to use instead the clumsy but widely-accepted term (or misnomer) “Arab Afghans.” [ZZ cf. fn 4 Chap 7]

[3]Guardian, 1/7/93; Evan F. Kohlmann, Al-Qaida’s Jihad in Europe: The Afghan-Bosnian Network (Oxford and New York: Berg Publishers, 2004), 16. Despite this public stance, ISI elements “privately” continued to support Arab Afghans who were willing to join Pakistan’s new covert operations in Kashmir.

[4]Montasser al-Zayyat, The Road to Al-Qaeda: The Story of Bin Lāden’s Right-Hand Man (London: Pluto Press, 2004), 55.

[5] Barnett Rubin, New York Times, 12/28/92.

[6] Robert Baer, Sleeping with the Devil (New York: Crown, 2003), 143-44. Former CIA officer Robert Baer, who in 1993 was posted to Tajikistan, describes a raid at that time in which “a Tajik Islamic rebel group…from Afghanistan…managed to overrun a Russian border post and cut off all the guards’ heads.” According to Baer, the local Russian intelligence chief was convinced that “the rebels were under the command of Rasool Sayyaf’s Ittehad-e-Islami, bin Laden’s Afghani protector,” who in turn was backed by Saudi Arabia and the IIRO. More commonly it is claimed that Hekmatyar’s terrorist drug network was supporting the Tajik resistance (Independent, 2/17/93, San Francisco Chronicle, 10/4/01). For Casey’s encouragement of these ISI-backed raids in 1985, see Steve Coll, Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (New York: Penguin Press, 2004), 104.

[7] Michael Griffin, Reaping the Whirlwind: The Taliban Movement in Afghanistan (London: Pluto Press, 2001), 150 (Tajik rebels); Coll, Ghost Wars, 225 (U.S. aid).

[8] Ahmed Rashid, Jihad: The Rise of Militant Islam in Central Asia (New Haven: Yale UP, 2002), 140-44.

[9] Griffin, Reaping the Whirlwind, 115. Exploration in the 1990s has considerably downgraded these estimates.

[10] Ahmed Rashid, Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia (New Haven: Yale UP, 2001), 145.

[11] Peter Dale Scott, Drugs, Oil, and War (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), 30-31.

[12] Martha Brill Olcott, “The Caspian’s False Promise,” Foreign Policy, Summer 1998, 96; quoted in Michael T. Klare, Blood and Oil: The Dangers and Consequences of America's Growing Dependency on Imported Petroleum(New York: Metropolitan/ Henry Holt, 2004), 129. Cf. Scott, Drugs, Oil, and War, 8, 64-66.

[13] Reuters, 4/24/05.

[14] Martha Brill Olcott, Washington Post, 5/22/05

[15] Thomas Goltz, Azerbaijan Diary: A Rogue Reporter’s Adventures in an Oil-Rich, War-Torn, Post-Soviet Republic (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1999), 272-75. Cf. Mark Irkali, Tengiz Kodrarian and Cali Ruchala, “God Save the Shah,” Sobaka Magazine, 5/22/03, http://www.diacritica.com/sobaka/2003/shah2.html. A fourth operative in MEGA Oil, Gary Best, was also a veteran of North’s Contra support effort. For more on General Secord’s and Major Aderholt’s role as part of Ted Shackley’s team of off-loaded CIA assets and capabilities, see Jonathan Marshall, Peter Dale Scott, and Jane Hunter, The Iran-Contra Connection: Secret Teams and Covert Operations in the Reagan Era (Boston: South End Press, 1987), 26-30, 36-42, 197-98.

[16] It was also a time when Congress, under pressure from Armenian voters, had banned all military aid to Azerbaijan (under Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act). This ban, reminiscent of the Congressional ban on aid to the Contras in the 1980s, ended after 9/11. “In the interest of national security, and to help in `enhancing global energy security’ during this War on Terror, Congress granted President Bush the right to waive Section 907 in the aftermath of September 11th. It was necessary, Secretary of State Colin Powell told Congress, to `enable Azerbaijan to counter terrorist organizations’" (Irkali, Kodrarian and Ruchala, “God Save the Shah,” Sobaka Magazine, 5/22/03).

[17] Richard Secord, with Jay Wurts, Honored and Betrayed: Irangate, Covert Affairs, and the Secret War in Laos (New York: John Wiley, 1992), 53-57.

[18] Secord, Honored and Betrayed, 211-16.

[19] Secord, Honored and Betrayed, 233-35.

[20] Goltz, Azerbaijan Diary, 272-75; Peter Dale Scott, Drugs, Oil, and War (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), 7. As part of the airline operation, Azeri pilots were trained in Texas. Dearborn had previously helped Secord advise and train the fledgling Contra air force (Marshall, Scott, and Hunter, The Iran-Contra Connection, 197). These important developments were barely noticed in the U.S. press, but a Washington Post article did belatedly note that a group of American men who wore "big cowboy hats and big cowboy boots" had arrived in Azerbaijan as military trainers for its army, followed in 1993 by “more than 1,000 guerrilla fighters from Afghanistan's radical prime minister, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.” (Washington Post, 4/21/94) Richard Secord was allegedly attempting also to sell Israeli arms, with the assistance of Israeli agent David Kimche, another associate of Oliver North. See Scott, Drugs, Oil, and War, 7, 8, 20. Whether the Americans were aware of it or not, the al Qaeda presence in Baku soon expanded to include assistance for moving jihadis onwards into Dagestan and Chechnya.

[21] Cooley, Unholy Wars, 180; Scott, Drugs, Oil, and War, 7.

[22] Cooley, Unholy Wars, 176.

[23] As the 9/11Commission Report notes (58), the bin Laden organization established an NGO in Baku, which became a base for terrorism elsewhere. It also became a transshipment point for Afghan heroin to the Chechen mafia, whose branches “extended not only to the London arms market, but also throughout continental Europe and North America (Cooley, Unholy Wars, 176).

[24] Mark Irkali, Tengiz Kodrarian and Cali Ruchala , “God Save the Shah: American Guns, Spies and Oil in Azerbaijan,” 5/22/03, http://www.diacritica.com/sobaka/2003/shah.html. As we have just seen, they were not the first.

[25] One of Bin Laden’s associates claimed that Bin Laden himself led the Arab Afghans in at least two battles in Nagorno Karabakh. (Associated Press 11/14/99).

[26] Ibrahim Eidarous, later arrested in Europe by the FBI for his role in the 1998 embassy bombings, headed the Baku base of Al Qaeda between 1995 and 1997 (Strategic Policy 10/99). An Islamist in Baku claimed that they did not attack the U.S. Embassy there so as "not to spoil their good relations in Azerbaijan" (Bill of Indictment in U.S.A. vs. Bin Laden et. al. 4/01; Washington Post 5/3/01).

[27] Cooley, Unholy Wars, 176.

[28] Frank Viviano, San Francisco Chronicle, 12/18/92.

[29] 9/11 Report, 58.

[30] USA vs. Osama bin Laden, Transcript, Testimony ofJamal Ahmed al-Fadl, February 6, 2001, http://cns.miis.edu/pubs/reports/pdfs/binladen/060201.pdf, 300-03.

[31] Levon Sevunts, Montreal Gazette, 10/26/99; cf. Michel Chossudovsky, “Who Is Osama bin Laden?” Centre for Research on Globalisation, 9/12/01,

http://www.globalresearch.ca/articles/CHO109C.html. Those trained by ISI included the main rebel leaders Shamil Basayev and Al Khattab. Cf. Rajeev Sharma, Pak Proxy War: A Story of ISI, bin Laden and Kargil (New Delhi: Kaveri Books, 2002), 84, 86, 89, 91.

Masters of the Pipelines

As Michael Griffin has observed, the regional conflicts in Nagorno-Karabakh and other disputed areas, Abkhazia, Turkish Kurdistan and Chechnya each represented a distinct, tactical move, crucial at the time, in discerning which power would ultimately become master of the pipelines which, some time in this century, will transport the oil and gas from the Caspian basin to an energy-avid world.[32]

The wealthy Saudi families of al-Alamoudi (as Delta Oil) and bin Mahfouz (as Nimir Oil) participated in the western oil consortium along with the American firm Unocal.

It is unclear whether MEGA Oil was a front for the U.S

It is unclear whether MEGA Oil was a front for the U.S